The Great Vowel Shift

Author: Tori Strickling

| Table of Contents | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Shifting Vowels |

| 2 | The Great Vowel Shift |

| - | Long Vowels |

| - | Effect |

| - | Evidence of the Shift |

| 3 | Current Vowel Shift |

| 4 | References |

Shifting Vowels

As you know, language is in a constant state of change. Phonology is no different, and vowels are particularly prone to evolution owing to their less specific manner and place of articulation.[1] Do you know the precise height of your /i/ vowel? In reality, every time you pronounce a vowel, there are likely subtle differences in tongue placement, and the unique geometry of your mouth effectively means that your vowels are unique compared to your friends’. So vowel realizations are not constant among a community of speakers or even within your own speech!

These distinctions in vowel pronunciation are usually imperceptible, but sometimes these changes are recurrent and significant enough to constitute an actual change in the phonetic characteristic of the vowel, known as vowel shift.[1] These vowel shifts are of interest to linguists, who often name them in terms of a transformation of the place of articulation. For example, if a linguistic trend was discovered where speakers pronounced /stɑp/ as [stap], it might be termed “a-fronting” because the new value [a] is achieved by moving the tongue forward from [ɑ].

But how do these significant shifts occur in entire speaker populations? It is important to realize that the process is fairly slow and that a single speaker will not notice a difference in their own speech through their lifetime. Rather, younger speakers develop subtly distinct pronunciations than older, conservative speakers and this continual cycle eventually amounts to a noticeable difference.[2] By this time, the pre-shift speakers are either deceased or very old: you might have noticed your elderly relatives pronouncing certain words strangely to your ear, though as the world changed around them, their own speaking style might have changed in effect. Sometimes, speakers can notice vowel differences in their own speech, where two or more pronunciations of a word are equally valid. Perhaps this occurs for you in the word “route”: do you pronounce it as both [ɹut] or [ɹaʊt] — or if you have a more distinctive accent, perhaps neither of those were accurate and you say [ɹʊt] or [ɹʌʊt]. If you believe that multiple pronunciations are accurate in your accent, your speech community might be in the middle of vowel shift for this word.[2] If you believe, however, that one is correct and the other is characteristic of another accent then perhaps your variety of English already underwent a vowel shift for this word, or never underwent one.

The Great Vowel Shift

The Great Vowel Shift targeted the long vowels of English from the 15th to 18th centuries.[2] The change in vowel quality was so marked, that spoken English before the shift would likely be unintelligible to you. The overall shift can be described as a raising process.[2] Linguists are unsure what caused the Great Vowel Shift, though the primary theories center around social upheaval of the era that brought speakers of various dialects together.[3] Interestingly, the orthography of English was being standardized during this era so the sometimes confusing spellings we see today are a result of the transitory state of the phonology.[4]

Long Vowels

What exactly are the long vowels of English? When you learned to read and write, your teachers probably taught you about silent ‘e’ and how it made the preceding vowel “long”. Perhaps all your life you understood /aɪ/ as “long i” — even the name of ‘i’ indicates this. But in linguistics, you have learned that [i] represents the sound you were taught was “long e”. If you know how to read other languages written in Latin script, you have probably noticed this disconnect between their vowel names and qualities and English’s. What gives?

Vowel length is actually the duration of the vowel sound; long vowels are notated with /:/ in narrow IPA transcriptions.[5] In some languages this is contrastive, meaning a minimal pair can be selected where the only phonetic difference to select the second meaning is vowel length.[5] In English, however, vowel length is conditioned phonologically so you do it automatically and will not normally notice it. Try saying the words “bit” and “beat”.[6] If you pay close attention, you might notice that the vowel in “beat” is longer in duration that that in “bit”. If you do not believe this, try recording your self and watch the waveform.

In English, the long vowels are /e/, /i/, /o/, and /u/. Diphthongs (adjacent vowels occurring in the same syllable) like /aɪ/ or /aʊ/ can also fall into this category of long vowels. In fact, in most varieties of English, long vowels like /o/ or /e/ are diphthongized: in common American dialects they are realized as [oʊ] and [eɪ], respectively. These modern realizations are the shifted versions of the long vowels before the Great Vowel Shift.

Effect

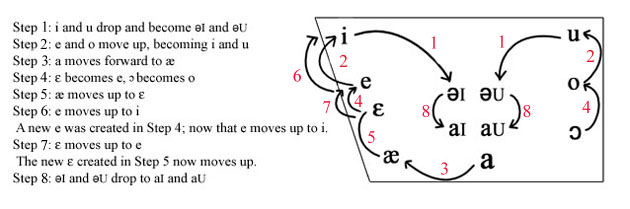

Before the Great Vowel Shift, the English long vowels had qualities similar to their values in the IPA. Thus, long ‘a’ was [a:] rather than [eɪ], long ‘e’ was [e] rather than [i], and long ‘i’ was [i] rather than [aɪ]. The figures below show detailed reconstructions of how the vowels may have shifted.

Schematic of Vowel Place of Articulation Transformations during the Great Vowel Shift:

Chart of Vowel Evolution during the Great Vowel Shift with Example Words:

As you can see, the original pronunciations of many common words were quite alien just 600 years ago, but the existence of a vowel shift helps explain their spelling. Additionally, it may be interesting to compare the vowel values around 1500 to modern Scots phonology, as much of the Anglicization of Scotland occurred around this time.

To hear example dialogues between a younger and older, conservative speaker during various stages of the Great Vowel Shift, try this link: http://facweb.furman.edu/~mmenzer/gvs/dialogue.htm. For an excellent overview of the stages of the Great Vowel Shift, try this lecture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zyhZ8NQOZeo.

Not all words underwent the vowel shift. One group of exceptions was many words using ‘ea’ that are not pronounced using /i/ like in “beach” or “year”. Many are pronounced are still pronounced as /e/ as in “great”, “break”, and “bear”. Others are still pronounced as /ɛ/ as in “bread”, “dead”, and “thread”. As another example, the word “you” is still pronounced [ju] while “thou” shifted to [ðaʊ], likely because the latter suffered disuse and its pronunciation was therefore based more on spelling.

Evidence of the Shift

While the Great Vowel Shift nicely explains the strange orthography of English, how do we know that it actually occurred? As with all historical linguistics, the models only represent linguists’ best guesses of past forms based on relationships between other languages.[7] Thus the pre-shift forms of many English words can be hypothesized based on their relationship to modern forms in other Germanic languages. But perhaps more compelling evidence comes from actual testimony of speakers during the era. How can people in the 1500s give testimony to how they spoke their language?

Originally, writers spelled the way they spoke because there was no standard orthography. By the time of the Great Vowel Shift, however, the spelling system was starting to be standardized and as such no longer unambiguously reflected the actual pronunciation of the writer.[8] We can, however, still see how people spoke English in this era by looking at the puns and rhymes they used in their literature. In many cases, this wordplay only makes sense if the Great Vowel Shift is taken into account.

Looking at the very beginning of the Great Vowel Shift, as Modern English began to arise from the Middle English language we see these examples from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales:

- And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

- And bathed every vein in such liquor

Of which virtue engendered is the flour; …

- And small fowles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

- And small fowl make melody,

That sleep al the night with open eye

As you can see, Chaucer rhymes “liquor” with “flour” and “melody” with “eye”: words that clearly do not rhyme in Modern English. This does not necessarily prove the exact past forms but it does indicate that a vowel shift occurred in those words.

In Modern English, Shakespeare gives us many good examples in the form of puns that would otherwise be missed by the modern reader. From Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1 we have this example:

Poins: Come, your reason Jack, your reason.

Falstaff: What, upon compulsion? No: were I at the Strappado, or all the Racks in the World, I would not tell you on compulsion. Give you a reason on compulsion? If Reasons were as plentie as Blackberries, I would give no man a Reason upon compulsion, I.

Did you get the joke? That reasons be as plentiful as blackberries? Remember that /i/ was historically /e/ so “reason” would be a homophone of “raisin”. Another example, from Midsummer Night’s Dream:

Pyramus: Now dye, dye, dye, dye, dye, dye.

Demetrius: No Die, but an ace for him; for he is but one.

Lysander: Lesse then an ace man. For he is dead, he is nothing.

Duke: With the helpe of a Surgeon he might yet recover, and prove an Asse.

In this case Shakespeare is punning on the fact that “ace” was a homophone of “ass”. More recent cases are common in nursery rhymes; perhaps you know of some. In the following example, “tea” is rhymed with “away”:

Polly, put the kettle on. Polly, put the kettle on. Polly, put the kettle on. We’ll all have tea.

Sukey, take it off again. Sukey, take it off again. Sukey, take it off again. They’ve all gone away.

Similar evidence is shown in John Dryden’s 1697 translation of Aeneis:

He calls to raise the Masts, the Sheats display; The Chearful Crew with diligence obey; They scud before the Wind, and sail in open Sea.

Careful study over the last century has uncovered countless examples such as these. Combined with knowledge of modern accents and the relationships between related languages, the Great Vowel Shift proves to be a compelling hypothesis.

Current Vowel Shift

Linguists have actually identified some vowel shifts that are currently underway. One particularly famous trend studied by linguist William Labov is the Northern Cities Vowel Shift.[9] It has targeted the short vowels in English with a more complex set of transformations than the Great Vowel Shift. Perhaps you know someone with whose speech is affected by this shift, or at least have seen tropes on TV of the stereotypical Minnesotan saying [bɪəg] for “bag” or [kʰæɹ] for “car”.

Of special interest to us at UC Davis is the vowel shift underway in Californian English. You might know that Californian English has already lost the /ɔ/ phoneme, rendering “caught” and “cot” homophones. According to Cory Holland’s sample of Californian speakers, another merger is underway. Specifically, back vowels are merged before /l/.[10] If you try saying “pull”, “pool”, and “pole” carefully you might disagree but during natural speech the vowels in these words become much less differentiated. With enough linguistic isolation, future speakers of Californian might wonder why these three words are spelled with different vowels just as we wonder why “you” and “house” are spelled with the same vowel. To read about other interesting findings about Californian vowel shift, you can read her research poster.

References

1. Labov, William (1994). Principles of Linguistic Change. Blackwell Publishing. p. 145. ISBN 0-631-17914-3.

2. Menzer, M., "What is the Great Vowel Shift?" http://facweb.furman.edu/~mmenzer/gvs/what.htm

3. Wolfe, Particia (1972). Linguistic Change and the Great Vowel Shift in English. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01835-4.

4. The Great Vowel Shift. http://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/vowels.html

5. "Vowel Length." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vowel_length

6. Menzer, M., "Terminology." http://facweb.furman.edu/~mmenzer/gvs/terms.htm#long

7. Li, C., "Reconstructing Ancient Languages"

8. Menzer, M., "English Literature and the GVS" http://facweb.furman.edu/~mmenzer/gvs/lit.htm

9. "Northern Cities Vowel Shift." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Cities_Vowel_Shift

10. Holland, C., "Shifting or Shifted? The state of California vowels" http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/SCIHS/abstracts/6_FridayPosters/Holland.pdf